We at HSP are following the news closely and keeping up with the potential impacts the pandemic will have on various cities and industries. This week, we are focusing on Minneapolis. We found the following article published in the Minneapolis/St. Paul Business Journal particularly insightful:

Ghost town: The downtown Minneapolis economy has been hit hard by covid-19, and a recovery remains elusive

Written by Nick Halter

Published on August 13, 2020

As restaurants and hotels in the suburbs and neighborhoods slowly bring back diners and guests, downtown Minneapolis has been left out of the modest recovery taking hold in the rest of the metro, and it could be months or even a year before the heart of the city even begins to rebound.

The downtown Minneapolis economy relies on an estimated 216,000 employees who work in office towers, behind bars, in hotels and at entertainment venues.

However, with office building managers reporting 10% to 15% occupancy and a complete wipeout of sporting events, conventions, concerts and theater, just a fraction of those workers are coming to downtown on a given day.

And it shows. Roughly 90% of skyway restaurants and shops had not reopened by July. Most of the street-level restaurants on and around Nicollet Mall, like Mercury Dining Room & Rail, Devil’s Advocate, The Local, Zelo and 801 Chophouse, are also closed.

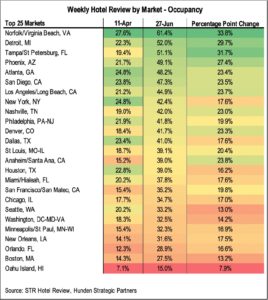

Parking revenue at city-owned ramps and meters is down 73% since April, and downtown hotel occupancy has declined by north of 80% this summer, according to STR, a hospitality data firm based in Hendersonville, Tenn. Twice as many rooms in the suburbs are full compared to downtown.

Sales tax revenues driven largely by downtown restaurants and hotels have dropped 46% since April 1, according to city of Minneapolis data.

But the worst news has been trickling out over the past two weeks. First, the Minneapolis school district announced an all-virtual start to the school year, and then Gov. Tim Walz announced a statewide schools plan that will keep many kids learning from home, at least part of the time. Big employers who had been targeting early September to bring their workers back have kicked that decision further down the road.

“There has been some original thinking that Labor Day was kind of a line in the sand with regards to some employers coming back,” said Minneapolis Regional Chamber of Commerce CEO Jonathan Weinhagen. “We are increasingly hearing that be pushed out to the end of the year and into 2021.”

If office workers don’t return until 2021, the consequences for downtown could be dire.

No return in sight

Technically, an executive order by Walz still requires nonessential employees who can work remotely to continue to do so. Corporations would be breaking that order if they brought workers back.

Even if Walz did lift that order, many of the city’s largest employers are showing no signs of rushing back. And that’s frustrating to Paul Wischermann, whose company Wischermann Partners manages Hotel Ivy and The Marquette Hotel downtown.

He has a message for corporate employers who have long been supporters of the community through their philanthropic efforts: Bring your workers back.

“Using the word safety or pandemic, in order to not bring people downtown, has other consequences,” Wischermann said. “Our community will suffer from it for years, for a decade. I’m not saying we shouldn’t be safe. I’m not saying we shouldn’t social distance or not wear a mask. But I do believe that we can contribute to bringing commerce back to downtown, and there doesn’t seem to be a willingness to do that.”

One of the city’s most prominent hotels, the W Minneapolis-The Foshay, has fallen delinquent on its loan and the publicly traded owner, Dallas-based Ashford Hospitality Trust, informed its investors in July that it would be taken by a lender and sold.

Typically, Wischermann said, downtown hotel occupancies are around 80% in the summer, which is a peak time thanks to festivals, family celebrations and concerts. Business travel drives room rentals Monday through Wednesday night and tapers off on Thursday. With no corporations in the office, there’s no one coming to visit them.

“There’s a lot of leisure traveling happening,” Wischermann said. “If you look at occupancies, you will see that Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday, which usually are very busy times, there’s almost no business.”

Minneapolis Downtown Council CEO Steve Cramer said he understands the sentiment that corporations should bring workers back in order to help the downtown economy, but that first the business community and agencies like Metro Transit have to prove that it can be done safely.

“Arm twisting or appeals to [corporations’] obligation to keep downtown strong, I don’t think that’s the right argument,” Cramer said. “I think the best argument is demonstrating that it’s safe and secure, and that’s when companies will respond.”

Being realistic: July 2021

Doug Sams has little optimism that workers will come back downtown in significant numbers before July 2021. The owner of three downtown skyway D. Brian’s Kitchen & Catering restaurants, Sams has been paying close attention to what corporations are saying, and he doesn’t think many will return until there’s a vaccine that has been distributed to the population.

“I’m normally an optimistic person, and I try to keep my chin up and keep my attitude positive and march forward,” Sams said. “But I’m working on a roadmap to survive until July 1. Anything short of that is wishful thinking.”

Sams has reopened one of his three D. Brian’s in the skyway. He’s negotiated with his landlords on the other two. In one case, he’s negotiated a new lease in which he extended the term from one remaining year to six, but doesn’t have to pay rent until he reopens. On the other, which he had a 5-year term remaining, the taxes and common area maintenance (CAM) costs are being accrued and will be added on later.

“People say, ‘That’s a sweet deal. Your landlord’s only asking for the passthrough CAM and taxes,’ ” Sams said. “I tell them, ‘No, no, no. You don’t understand. That’s not a sweet deal because in a year from now you are going to owe them $100,000, and it’s going to be almost impossible to dig out.’ ”

Sams said landlords could evict restaurants, but if they do it’s not like they’re going to be able to find a new tenant to pay the rent.

Restaurant broker Dick Grones, president of Cambridge Commercial Realty, said landlords know that “oatmeal is better than no meal” when it comes to waiting on tenants who can’t pay their rent.

“I looked at a proposal the other day and this landlord — who I think is savvy — he’s offering the first nine months rent-free just to attract someone to the space,” Grones said.

Sams is optimistic about the long-term future of his restaurants, which also include suburban outposts. There’s been an overbuilding of restaurants in the country, putting supply and demand out of whack, he said. That oversupply has prevented restaurant owners from raising revenue through increased menu prices. The pandemic, which has been predicted to close between 30% and 50% of restaurants, will flip the equation.

“The teeter totter has switched,” he said. “There’s going to be too few restaurants for people who want to eat, and that’s what I’m looking forward to — the second half of next year.”

Residential population helps

Commerce isn’t just bad in the skyways, it’s bad on the street level.

Hen House Eatery in Baker Center is one of the few full-service downtown restaurants that has reopened.

A popular business breakfast and lunch spot has a spacious dining room and sidewalk patio. On a recent Wednesday afternoon in July, the restaurant was at half capacity, but instead of suits and ties, customers were wearing Tshirts and shorts.

“During the week, Monday through Friday, it was around 90% business people,” co-owner Barb Gardiner said of Hen House customers before Covid-19. “We have had a few here and there who are coming back to the office, but not a lot.”

Hen House takes phone numbers from customers making reservations, and that’s revealed a lot of people who are visiting the city from out of town. There’s also a lot of downtown dwellers getting out of their apartments for a meal.

The downtown residential population has increased by 60% since 2006, to 51,000, according to Minneapolis Downtown Council estimates.

“Growing the residential base downtown has helped soften the blow a little bit,” Cramer said. “We’re seeing some evidence that there’s a softening of demand for downtown housing, but there hasn’t been a big spiraling that’s been noticed at this point. Hopefully that population is going to hold.”

Sales at Hen House are down 50% compared to pre-Covid levels as the restaurant pieces together a business with a half-full dining room, a sidewalk patio and a little bit of catering work for hotels that shut down their restaurants, Gardiner said. Hen House has reduced its number of servers from 10 to two.

Surprisingly, Gardiner said the current situation is sustainable.

“The margins are tight, but we can still do it,” she said.

Others haven’t fared as well. The list of restaurants permanently closing downtown locations includes McCormick & Schmick’s, 4 Bells and popular skyway lunch spot Allie’s Deli.

Police debate

Downtown Minneapolis, like so many other downtowns across the country, will need to dig itself out of a deep hole when Covid-19 is under control. However, some business leaders say Minneapolis has a steeper climb because of public safety concerns.

Cramer said he’s surveyed real estate brokers who are tracking downtown companies that, because of the Minneapolis City Council’s push to defund the Police Department, want to move out of downtown to the suburbs. The brokers also say there are suburban companies that have called off searches for office space downtown.

Weinhagen said he’s heard the same from companies. He hasn’t heard of a massive company looking to relocate, but big firms that might move some employees to other sites in the suburbs or elsewhere in the country.

“The good news is we’re still in active conversations with a number of companies that are looking at downtown and relocating into the city,” Weinhagen said. “But for every one of those we are hearing from employers who are saying, ‘Hold on a minute. We have real concerns about the direction the city is headed.’ A lot of that is a narrative problem. Out of the gate we heard this message of abolish the police. That has stuck with people. That’s what is really resonating with business leaders and with employees. And there’s real concern — the prospect of a city that doesn’t have a police department.”

City Council Member Steve Fletcher, who represents downtown, said the Minneapolis Police Department has lost the trust of a portion of the public and that must be fixed, because otherwise the police won’t be effective. However, he said the idea that the City Council would get rid of the department is false.

“We’ve certainly said some dramatic and bold things about transformative change, but we’re not abolitionists,” Fletcher said. “I think it is the Council’s view that we will have a police force. It will probably be smaller and more focused. And there will be other kinds of public safety support that people will see. I think there are some dramatically different ways that we can approach an awful lot of problems.”

City Council members have made varied — and at times conflicting — statements on their vision for what would come after defunding the police force, an effort now on hold after a vote by the city’s Charter Commission. Fletcher himself wrote in an opinion piece in Time magazine that he would support the disbanding of the Police Department.

Neither Cramer nor Weinhagen would identify a company that has said it is leaving the city. Weinhagen said companies don’t want to identify themselves because the matter has become so political and they don’t want to get sideways with the public.

A migration out of downtown would be a stark contrast to the trend over the past 10 years, as the city has seen a massive net migration of suburban companies relocating in order to attract younger talent. Between 2013 and 2019, downtown and the North Loop neighborhood have posted a net gain of 1.4 million square feet of office tenants, according to CBRE Group Inc. research released last year.

The only significant loss for downtown has been TCF Financial Corp., which moved 1,150 corporate jobs to Plymouth in 2014. The company cited a need for a bigger space, reduced real estate costs and parking.

Wischermann said he’s worried that downtown is getting a bad reputation because of local and national media attention being paid to the civil unrest and efforts to defund the police. He said leaders need to communicate that the city is safe.

Wischermann said a group of 3M Open golfers had originally planned to stay at a downtown hotel during the July tournament, but backed out because they didn’t want to be downtown. (This account was confirmed by a source involved in the 3M Open.)

Will downtown ever be the same?

Every February, the Downtown Council holds a big annual gala to talk about the progress at the city core. In so many ways, the gala has celebrated an increasingly vibrant downtown that has been able to attract major sporting events, conventions, companies, residents and investment.

I asked Cramer, who has been at the helm of the Downtown Council since 2013, if Covid could unravel all of that progress, especially if some number of employees continue working from home permanently.

“It’s been a heavy blow. There’s no doubt about it, and we’re not through it yet,” Cramer said. “When we get through it, there’s going to be some kind of new baseline for our downtown economy, measured in restaurants that are open for business, permanent daytime workers and all the things that we measure as the signs of vitality for downtown. It’s going to be a lower new baseline. But we’ll settle into that baseline at some point and then we’ll begin to build back from there. I don’t think this is by any stretch of the imagination the death knell of our downtown or for any downtown.”